I’m often interested in the thinking of people whose agendas are radically opposed to mine. I’ve read more books by Hayek than Keynes. I’ve read Mein Kampf. Twice. And I’ve read the foundational authors of elite theory. Back in 2018 my interest in elite theory led to my becoming aware of a writer who publishes under the pseudonym Bronze Age Pervert (Amazon told me I’d like him because of the other books I’ve read, that were also written by terrible people). I skimmed some of BAP’s writing, and wasn’t very impressed. But when his name came up again recently, as part of the supposed intellectual foundation of Elon Musk and Peter Theil, I got curious about another name on the list of tech bro influencers: Mencius Moldbug, aka Curtis Yarvin. I did a little reading about Yarvin, and (again) wasn’t very impressed — except that I saw him quoted as saying something that struck me as interesting [bold added for emphasis]:

What is government? A government is just a corporation which owns a country. Nothing more, nothing less. It so happens that our sovereign corporation is very poorly managed and there’s a very simple way to replace that, which is what we do at all corporations that have failed. We simply delete them.

That description, “a corporation which owns a country,” was the bit that jumped out at me because if you think a government is “a corporation which owns a country,” then the United States is a grossly undervalued corporation. By which I mean that the market value of the assets owned by the United States — the stuff actually owned by the U.S. government, like the public lands, mineral reserves, and so on — is something like $5.7 trillion. Possibly more. So if you imagine the cost of taking total control of the national government as the buyout price for the corporation that currently owns them, it’s a small fraction of what the assets are worth. Corporations with large pools of unencumbered assets, that are grossly undervalued, are typically torn to pieces by asset-stripping. The asset-stripping model, as I understand it, goes something like this:

Be a private equity firm, and borrow a bunch of money.

Use the loan to buy a limited liability corporation that does something, and has a bunch of assets. Like, for example, a mining company.

Sell the mining company’s assets to your private equity firm and lease them back to the mining company.

Have the mining company borrow a bunch of money on some pretense like an expansion.

Shift that money over to your private equity firm, and use it to pay off the loans you took out to buy the mining company. If the mining company’s credit is good enough for it to borrow more than you paid to buy it, so much the better. Take that money too.

Cut staffing, and crank up production to make the mining company look profitable on paper, and hide the deficits created by the debt. After a couple of good quarters that make it look like a “growth stock” (but before the long hours and short staffing cause too many of the remaining employees to quit) sell the company.

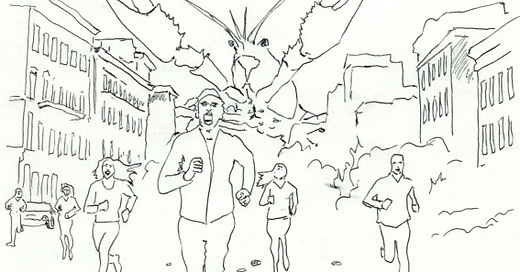

Park your yacht offshore, near the company headquarters, and use opera glasses to watch while it burns to the ground, as all the experienced employees leave, and the new owners realize they can’t maintain that productivity rate under high turnover. When the debt service rises up from below like a Balrog escaping the mines of Khazad-dûm, listen as the new owners try desperately to banish it with the blasphemous chanting of ancient rituals, performed in dead languages and mixed with the cries of their sacrificial victims (sound carries strangely over water). Watch the false sunrise grow on the horizon, hours before dawn, as the flames spread to the nearby town. Go below decks for another bottle of champagne, but find yourself strangely reluctant to go back to your deckchair as the sun finally rises. Realize you have become a demon, a servant of the Dark One, and that you must shun the daystar.

I’m sure I’m leaving some stuff out, but that’s the basic shape of the gag. The moral of the story is that a well-run company that has a few bad quarters, or a few bad years, is in much more danger than a poorly-run company that’s having trouble. The stock prices of both good and bad firms will dip in response to a change in relative performance. But if the stock price of a well-run company dips below the sell-off, or intrinsic value of the company, it will attract corporate raiders who want to strip it of its assets — assets it only has because it was well-run.

That’s more or less what happened to Red Lobster. Red Lobster had good years, and bad years, but they owned the real estate their restaurants were built on, with no mortgages. From an operational perspective, that kept their overhead low, which made them an extremely stable company that could offer food at lower prices than other restaurants, while still maintaining high standards. They had a few rough years, Golden Gate Capital bought them up, sold off that real estate, then sold the chain to another big firm that locked Red Lobster into supply deals. The bad supply deals, plus having to pay rent on land they used to own, sank the company.

What Elon Musk and Trump are doing to the U.S. government is a little different. But only a little. The other tools they’re using are pretty standard. Without getting into a lot of detail it works something like this:

The U.S. has a large pool of voters who want an impossible stupid thing. They’ll never get it, because it’s impossible, but the steps involved in pretending to give it to them will drive up the national debt to an unprecedented degree.

The debt has been a problem for the U.S. for a long time, but we’ve been protected from many of its harmful effects by a number of mechanisms. Our dollar is an important reserve currency for a lot of big economies, and our massive trade deficit means a lot of other countries have an interest in propping us up. If the U.S. economy really falls apart — if the dollar becomes worthless — China (for example) burns to the ground. Our dollar is also extremely important in international oil trading. So we keep printing dollars, and other countries keep taking them. But there is a tipping point, and we seem to be approaching it.

By leveraging the desires of the large pool of voters who want the impossible stupid thing, Trump and Musk were able to get control of a big chunk of the federal government.

Now that they have control, they’re breaking everything they can get their hands on, while also slashing revenues. This will cause the national debt to positively explode.

If they actually managed to push the debt past the tipping point, whatever that exact number may be, it opens the door to demands for us to pay it down by selling off assets. When the IMF does this to a developing nation, it’s called a structural adjustment loan. But if you want an idea of what it’ll look like here, you need look no further than what Trump just did to Ukraine with that minerals deal everyone was talking about for a while. When a country’s out of money, and desperate, you can make them sell you stuff. You can name the price.

Who’s going to buy U.S. resources under those conditions? I don’t know, but if I had to guess I’d look at the richest people on the planet. Like, for example, the five multi-billionaires who went to Trump’s inauguration.

What happens then, of course, is a giant question mark. But consider, if you will, the case of Queen Anne High School, in Seattle.

When I first moved to Seattle there was a high school on top of Queen Anne Hill that you could see from almost anywhere in the central city. It was this beautiful white masonry building, with amazing views of downtown Seattle, both mountain ranges, the Space Needle and the Puget Sound. Generation X was a lot smaller than the Baby Boom generation, so a lot of schools in Seattle closed when I was growing up, and Queen Anne High School was one of them. It closed in 1981. Seattle public schools were desperate for money all through the ‘80s, when the city’s tax base was at its absolute worst because of white fight. In 1986, a developer made a deal to convert Queen Anne High into apartments, and rent them out. So by the early ‘90s, you had apartments with 20’ ceilings, hardwood floors, and cute vintage chalkboards in them, renting into a gentrifying market for up to $2,200 a month. The School District got about $50 per unit of that rental income. The rest went straight into the developer’s pocket. Somewhere around 2000, the rental agreement turned into a purchase, to make the building into condos. The school officially went on the market in 2005, and the deal was settled in 2008. I still don’t know who in the government was responsible for the original deal that gave the rental developer an option to sell the building, but the Seattle School District got $4.8 million of the sale price of the building, out of something like $25 million. That building has 139 condo units in it. A one-bed, two-bath, top floor unit in what used to be Queen Anne High School went for $1.4 million last month.

This was classic asset stripping, as applied to government. However much these developers had to pay in kickbacks or lawyer’s fees, it more than paid off in the long run. The Seattle School District had an unprotected asset, they were broke, and a corporate raider swooped in and snatched it up. The key thing — the most important part — is that Seattle will never get that school building back. That cathedral on the hill, that you can see from the entire city, will only ever be a monument to what can happen to public assets when voters are asleep at the wheel.

Sound like any Last Remaining Superpower you might know?

Right. So now apply that model to, for example, Yosemite. Or, as Donald Trump likes to call it, Yo, Semite. I don’t know what Yosemite is worth on paper. I don’t know what percentage of the supposedly $1.8 trillion in U.S. real estate holdings Yosemite accounts for. But I bet if Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos were to buy it for its assessed value, they could double or triple their money in five years. Or think about the tidelands of Washington State. After statehood, Washington sold more than 70% of its shore-fronts to private interests, before the practice was stopped in 1971. Now you can’t walk on the beach in most of the state. But here, again, is the important question: could the state buy that land back? We all know the answer is “no.” However little the original buyers paid for that land, the people who own it now would demand so much for it that the state could never afford to buy it back. Now Trump is talking about handing more federal land over to the states. What could go wrong? Some of the alternatives are even worse. Trump might not even try to be sneaky about it. He might just liquidate public lands and send the money right onto the stock market. Gee, I wonder which companies he’d invest in.

I don’t know what to do about any of that. Voters need to start paying attention to this though. Once our public lands and monuments are gone, they’ll be gone for good. People like Trump and Musk will force us to sell them our birthright, and lease it back to us, like Golden Gate Capital did with Red Lobster’s restaurants. Mount Rainier, Yosemite, Yellowstone, Shenandoah — we could all live to see those become resorts we have to pay a private owner in order to visit. We could live to see them with No Trespassing signs around them. Hell, that could be the best-case scenario. Remember when the IMF forced the government of Bolivia to sell its rain to Bechtel? If that sounds crazy, try to register your kid for classes at Queen Anne High School, or go for a walk on the rocky shores of any of the San Juan Islands.